Structural Racism in Humanitarian Innovation

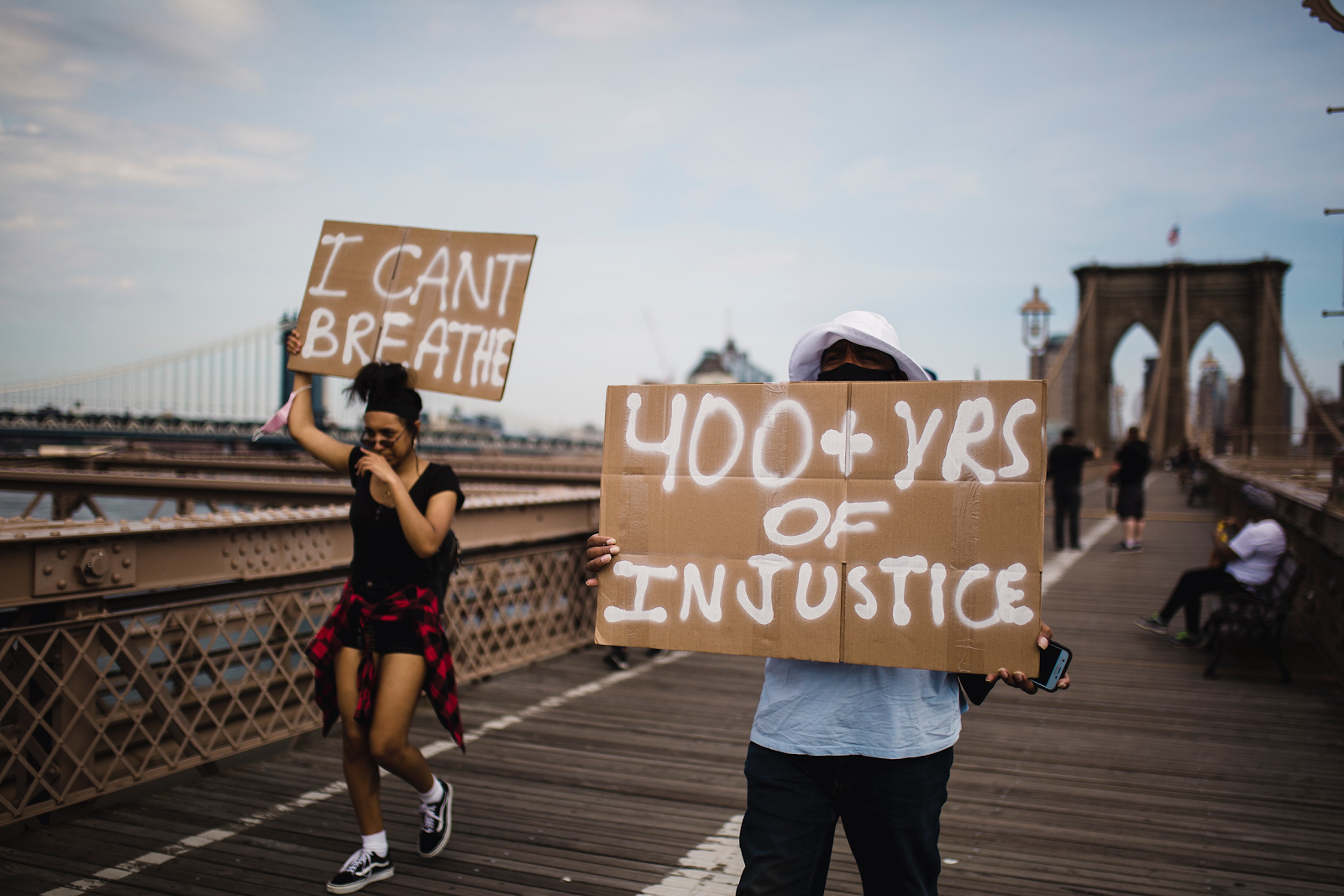

In the past couple of weeks, since the murder of George Floyd on the 25th of May, and the consequent rise in protests supporting the Black Lives Matter movement; I have taken the time to reflect upon my own personal situation and feelings towards the issues of race and social injustice. I have decided to use my role as a Humanitarian Liaison Officer at InAGlobe Education as a platform to express the company’s goals and my views with regards to dealing with racism in society. InAGlobe Education seeks to address societal racism and give people of all ethnicities and backgrounds an equal platform within the fields of innovation, design and engineering. With this blog post I seek to give a perspective on how structural racism is a part of development and also expand and develop InAGlobe’s position on certain issues. This will be done by exploring how technological innovation and collaborative design can be used to make the world a more equitable place by addressing the specific needs of the people we seek to innovate for.

A System for the “brain drain”

One of the main issues in the world, when it comes to design, engineering and innovation is that people tend to migrate and move to those cities that are globally known as technological or innovation hubs. In 2019, a study looking at industry and innovation indicators found that 20 of the world’s top 50 technological hubs were located in North America, with New York City and Silicon Valley ranked 4th and 3rd respectively. A further 18 were located on continental Europe with Paris, France and London, England ranked 2nd and 9th (Leskin, 2019). That is to say, 38 of the 50 most innovative and technologically advanced cities were located in what is commonly referred to as ‘the West’. The rest of the list had cities from Asia and the Middle East with Tokyo, Japan being considered the number 1 city in terms of innovation and technology. Even though lists which rank cities according to certain indicators can only be generalisations and subjective (as the indicators used to make these judgements cover broad spectra based on biased definitions), it is still glaringly clear that the Global South is not represented in this particular ranking. This can be due to a lack of sensitivity of the indicators and an insufficient amount of access given to opportunities or resources. The Global South is redefining the way in which technological innovation happens and is therefore maybe not on this list. For example using a 3D printer to create everyday items or medical equipment on a street corner in Kenya. The 3D printer is more robust and cheaper than the ones in Europe as it has been created by the locals for the locals. Is this not a form of technological innovation? By Western standards maybe not but in Africa, South America or places in Asia technological innovation means technology solutions that are environmentally and economically suited to the constraints faced in these places (Srinivasan, 2019).

A similar omission is evident when considering the world’s representation of technological hubs. Technological hubs are cities which foster and nurture innovation for startup businesses. As shown in the graph below technological hubs are not only leaders in innovation, but are also centres of economic and social growth and opportunity which draw skilled workers to them (Interquest Group 2019).

(Interquest Group, 2019)

The movement of people to these cities may be seen as progressive but it also lends itself to ‘The ‘brain drain’, a problem which affects the Global South in particular.

The brain drain is defined as the migration of highly skilled workers in search of higher standards of living, better access to technology and greater political stability. This phenomenon is most commonly seen in the migration of educated professionals from developing countries to developed countries in search of highly skilled jobs (Dodani and Laporte, 2005). The brain drain is not only subject to work, life and education but is also an issue when it comes to Higher Education where international students from developing countries, such as Africa will migrate to the United Kingdom or the United States of America to continue their studies. This last aspect of the brain drain – moving to a country to receive an education – resonates deeply with me as that is my current situation.

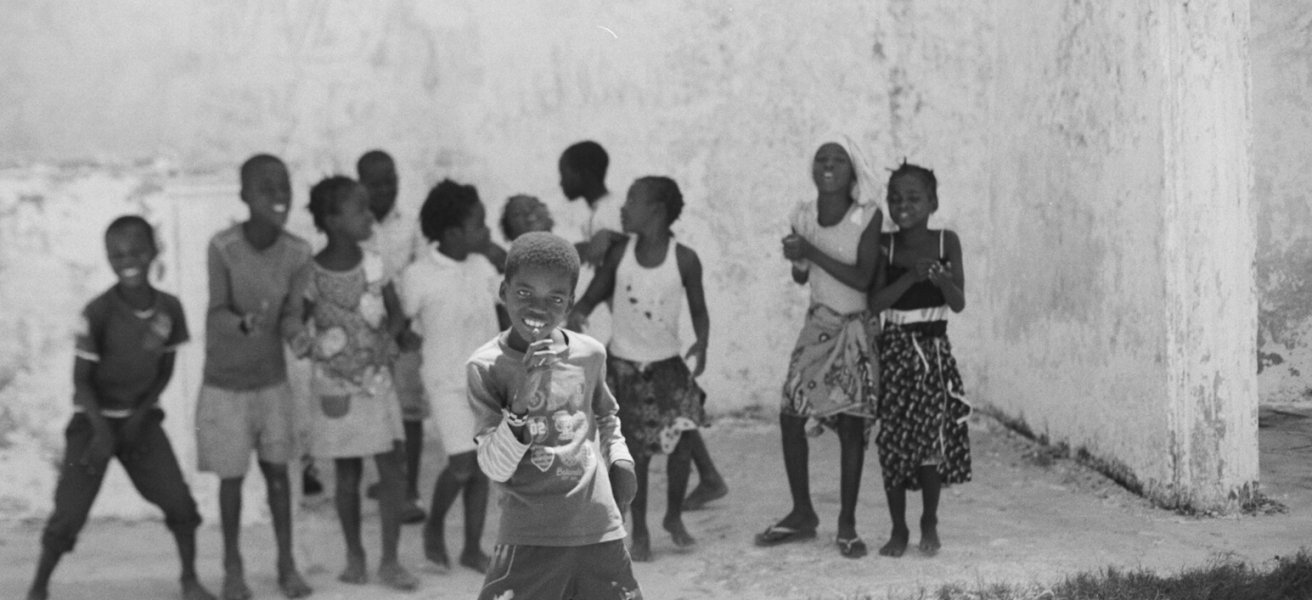

I was adopted as a baby from an orphanage in Nairobi, Kenya to Dutch and Kenyan parents. Growing up I have had the privilege to live in Switzerland for most of my life. This has allowed me access to a completely different lifestyle than if I had stayed in Kenya. My elementary and secondary school education was all achieved at an International School, after which I had the fortune of getting accepted into The University of Edinburgh for a four year undergraduate degree. These particular educational experiences have shaped my views on the world and allowed me to see the world from a privileged vantage point which leads me to wonder how people in Kenya view the world. I struggle a lot with this question and in-turn struggle to fully understand my Kenyan identity. This may not be the case for every person who has left their country either in search of a ‘brighter’ future or different opportunities but I find that this is the case for me. This is why I like to help the world through development.

The few times that I do go back to Kenya and see my mother’s family, I always see a disconnect between what I have learnt growing up and what actually occurs in Nairobi, Kenya. Life in Kenya can be considered more of a real world experience and one that is not subject to the sheltered life of growing up in ‘the West’. There is a disconnect, in this regard, between what I was taught in school and what actually occurs on the ground level in developing countries. The way that today’s society is structured encourages people to move to areas with the most technological advancement and innovation occurring to succeed but at the expense of learning what is occurring in one’s homeland. This knowledge must be found out independently which should not be the norm. Non-western perspectives and ideas should be appreciated and valued in education and in life as the world belongs to all of us, and never have we been as connected as now. I feel as though this mentality of not looking at the whole picture is not only a product of the geographical and socio-economic gaps between countries in the developing world and the developed world, but also touches upon the larger issue of structural racism across the globe which affects the way in which innovation and ethics in design are projected on developing countries from their ‘Western’ counterparts. It is therefore important to acknowledge the structure of development aid if we aim to change the world.

Pitfalls of Developmental Aid

One of the ways technological and design innovation occurs in developing countries comes through external monetary funding . The most common source of external funding in less economically developed countries comes from development aid, a process whereby countries receive financial aid in the hopes of stimulating economic growth and allowing developing countries to invest in better resources, infrastructure and tools (Olanrele and Ibrahim, 2015). A lot of resources are being dedicated to Development Aid or what is more colloquially known as foreign aid. This is a bracket term for the voluntary flow of capital from one country to another as it helps a country develop but, this does not necessarily help the developing countries (Kenton, 2020). Monetary aid and investment into a technological advancement is an important part of the world’s global economy and human needs, but ultimately, who gains from these transactions? It is hard to tell where this money goes as issues of corruption, lobbying and under the table diplomacy can undermine the way that foreign aid is meant to help. The United States alone spends about 50.1 Billion dollars per year in foreign aid to developing countries (Agarwal, 2019) and the European Union also spends over 50 Billion euros on aid per year under the bracket of advancing global development (European Commission, 2020) but if the structure of the system is flawed what does this money actually go to fund? Although a priori, there is nothing wrong with combating poverty and advancing aid through these measures. There may just be alternative ways of furthering technological development aid through a more transparent system whereby different people can contribute to how technological advancements can be made. This can be done through the inclusion of all the stakeholders no matter where they are located in the world.

At school I got taught about financial foreign aid and its pros and cons. The obvious pros being an injection of money into countries for development and greater technological advancements which on the surface seems like a massive step-forward. The cons being that there are financial and non-financial attachments to this aid that not all less economically developed countries manage to comply with. This means that countries can end up indebted to others or needing more help which raises the question of is aid worth it? The more I thought about it though, and the older I become I started questioning this whole system. Historically, modern colonialism refers to the time when European countries have colonised indigineous lands in Africa, the Americas and parts of Asia. This is also known as the ‘Age of Discovery’ which takes away from the lack of regard towards human rights which colonists showed towards their colonies. Colonists took away valuable resources, degraded the environment, created economic instability and ethnic rivalries but most importantly, killed human lives in the process. They then used these resources to build trading empires and profit from a system based on subjugation and exploitation (Blakemore, 2019). Many countries are guilty of this. The Netherlands with the Dutch East India Trading Company or the East India Trading Company which came out of England. Their empires are built on the work and death of people who were born in the countries they colonised leading to the growth of continental Europe over the centuries.

Noticing the imbalance in the world and human equality, countries started to invest in their former colonies and the developing world. This culminated in reaching a point in the past where development aid became a global phenomenon which people, countries, governments and organisations strive to achieve. Yet the aid which is given out to developing countries, to help with development, comes with strings attached to it. I find it a bit bemusing to consider when the reason developing countries are in the situation they are in is due to the product of colonialism and the loss of their countries resources over the years. It is almost as if the western countries and organisations have grouped together and acknowledged the fact they are the cause for the inequality but they also then tell others how their development should proceed. Imposing their ideas on others and saying, ‘This is the right way for a country to develop. You must develop the way we want you to develop.’ Is this not a form of postcolonial structural racism? They are helping the developing world but they are also helping themselves in the process and creating a narrative for how change should occur. The structure of the system that has been put into place favours one set of people and discriminates against others. Those who have the opportunity to help are still gaining at the end of the day. Even though it comes from a place of goodwill. What are we to do then when such a structure exists? Personally, I felt quite aggravated when this realisation of a rigged system dawned on me.

I know a few people who work in the world of development aid and they acknowledge that the development system is not perfect. The work that is being done through NGOs and multinationals is important and does help improve the world. I just like to reflect upon if there is a different, more equitable way to deliver development which does not come with the attachment of strings and conditions to it. There must be more transparency in this regard or maybe the system can be viewed from a different perspective, one based more on collaboration between people and on the specific needs of those in need. This is why I firmly believe in the advancement of technological and innovative development through collaborative design.

Collaboration as ‘King’

Collaborative design is an approach used to find non-linear solutions to problems. This occurs when different stakeholders actively take part in the design process, As opposed to the engineer or design expert saying what the final product will be. A process of engaging with the stakeholders and seeing what their specific issues are and based on these issues the co-creation of a product can be developed (Da Cunha Pimenta, 2018). In other words you are giving each stakeholder some level of autonomy and agency to put forwards their ideas. This relates to innovation in development because it is about giving people a voice to express their thoughts and needs. One thing I have learnt growing up is that even though I am a Kenyan citizen and national, I have no idea what the people in Kenya actually need to help with their development needs. I also do not have the right to superimpose my opinion onto other people about what I think they should do to foster development and innovation. Just because I have an education and a degree does not give me the right to tell other people that I know better than them because I cannot fully understand their circumstance. Through this process of collaborative design, the stakeholders in developing countries will be given a voice to say what their needs are as no two countries or organisations will have the same issues. They may be similar issues which will require similar solutions but these may have to be met with different specifications on the final design. It is also important to realise that some places may not even be able to implement or use the newest forms of technology as in their country they do not have the required resources, technological understanding or infrastructure to deal with new equipment and support widespread adoption (Becker, 2017). Even though the challenge may be the same, the context may not, and that will radically change the effectiveness of a given solution.

Collaborative design is an approach used to find non-linear solutions to problems. This occurs when different stakeholders actively take part in the design process, As opposed to the engineer or design expert saying what the final product will be. A process of engaging with the stakeholders and seeing what their specific issues are and based on these issues the co-creation of a product can be developed (Da Cunha Pimenta, 2018). In other words you are giving each stakeholder some level of autonomy and agency to put forwards their ideas. This relates to innovation in development because it is about giving people a voice to express their thoughts and needs. One thing I have learnt growing up is that even though I am a Kenyan citizen and national, I have no idea what the people in Kenya actually need to help with their development needs. I also do not have the right to superimpose my opinion onto other people about what I think they should do to foster development and innovation. Just because I have an education and a degree does not give me the right to tell other people that I know better than them because I cannot fully understand their circumstance. Through this process of collaborative design, the stakeholders in developing countries will be given a voice to say what their needs are as no two countries or organisations will have the same issues. They may be similar issues which will require similar solutions but these may have to be met with different specifications on the final design. It is also important to realise that some places may not even be able to implement or use the newest forms of technology as in their country they do not have the required resources, technological understanding or infrastructure to deal with new equipment and support widespread adoption (Becker, 2017). Even though the challenge may be the same, the context may not, and that will radically change the effectiveness of a given solution.

Collaborative design is an area in development that I feel quite passionate about. It has given me the opportunity to get into contact with small scale humanitarian organisations who do development aid work locally. This also allows the opportunity to hear first hand from people about their opinions on projects as well and targeted projects can be created. I feel that I can start to become deeply invested in projects which I am a part of and help develop the world whilst practicing transparency. In this way a more equitable platform for technological development can be created whereby all stakeholders are involved, regardless of race.

InAGlobe as a platform for co-design

InAGlobe Education sees itself as a platform which will enable a greater level of collaborative design to occur that directly involves the developing world. We see ourselves as a place which seeks to bridge the mismatch in information between those with the capacity to innovate (resources, expertise, etc.) and those living in low-resource environments. This process of creating collaborations with stakeholders on the ground will grant people more agency in making change in their country without structural pre-existing biases. This collaboration breeds a transparency and comradery that will be crucial in an evermore connected and globalised world that seems to be slipping along nationalist and exclusionary routes.

We believe that students that get involved in humanitarian engineering and innovation will also learn about how their work can be a direct benefit to those living in low-resource environments. It is also an opportunity to teach and educate students at University that collaborating with people outside of their immediate circles, and especially academic circles, can breed awesome results, as well as a better understanding of contexts so far detached. People who live in situations where development is needed will be able to give first-hand insights into their everyday problems and better specify how others can help. We envision that small scale projects that are highly collaborative can compound to have a massive effect internationally in the long run. This may occur through the simple act of thinking critically about a challenge, or my spinning out social enterprises that build the economy and provide jobs, as well as products and services directly stipulated by the community.

I would like to hope that this also leads to the creation of a train of thought in students who have had the privilege to grow up in the West that, in some circumstances, what may seem a rudimentary and somewhat simplistic technological design for them may in fact be of a vast benefit to a person in a developing country. It is through education that we learn about the world’s past grievances and how best to fix them. Through this active involvement of project creation, there is also hope that people learn to understand and accept people from different backgrounds and ethnicities as they team-up to tackle challenges that really involve all of us. Although this is not an outright dismantling or toppling of the structural and institutional racist inequalities in the world it does create a platform for change which promotes global acumen, and social and cultural awareness for people of developed nations and gives people in developing countries a platform to share their needs and have their voices heard. In this sense the technological hubs may not need to be located in cities such as London or New York but wherever people are, wherever those who have ideas for change are.

We stand behind the fact that Black Lives Matter, and that all ideas in-fact matter! We openly and candidly support a reconfiguration of all structures that present structural racism, and we invite everyone to open their hearts and minds to true collaboration.

Photo by Life Matters from Pexels

Written by Max Mwenda Wilbers, Humanitarian Liaison Officer at InAGlobe Education.

References:

Agarwal, P. (2020) Foreign Aid. [online] Intelligenteconomist.com.

Becker, A. (2020) Ldcs And The Technological Revolution | LDC Portal. [online] Un.org.

Blakemore, E. (2019) What Is Colonialism. [online] nationalgeographic.com.

Da Cunha Pimenta, G. (2018) Collaborative Design Sessions 101. [online] UX Collective.

Dodani, S. (2005) Brain drain from developing countries: how can brain drain be converted into wisdom gain?. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 98(11), pp.487-491.

European Commission – European Commission. (2020) Recipients And Results Of EU Aid.

InterQuest Group. (2020) The Biggest Tech Hubs In The World 2019 | Interquest Group.

Katz, D. (2018) Top-Down Vs. Bottom-Up Innovation. A Battle For Resources.. [online] Bbntimes.com.

Kenton, W. (2020) Foreign Aid. [online] Investopedia.

Leskin, P. (2018) The 50 Most High-Tech Cities In The World. [online] Business Insider.

Olanrele, I & Ibrahim, T. (2015). Does Developmental Aid Impact or Impede on Growth: Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues. 5. 288-296.

Srinivasan, R. (2020) Opinion: The Global South Is Redefining Tech Innovation. [online] Wired.